A humble name for a place that has been a refuge for minds wandering in search of meaning is Nizamuddin in Delhi. There’s a bookshop named JMC Emporium that has no door, no security, no window, no guard just books. The shelves simply begin where the street ends, and the hum of the bazaar is swallowed by the books. It feels like a cave of books. Some spines are cracked, others still hold their character, the corners of certain covers are curled by too many hands. It is the kind of place where you don’t ask for the latest bestseller. You let the book corner choose you. And there’s Basit. I have known him for a few years, not just as the man who sells books in Nizamuddin, but as one who seems to live in them. He does not recommend; he prescribes. “Books,” he once said, “are like medicine the wrong one can kill your appetite for the cure.”

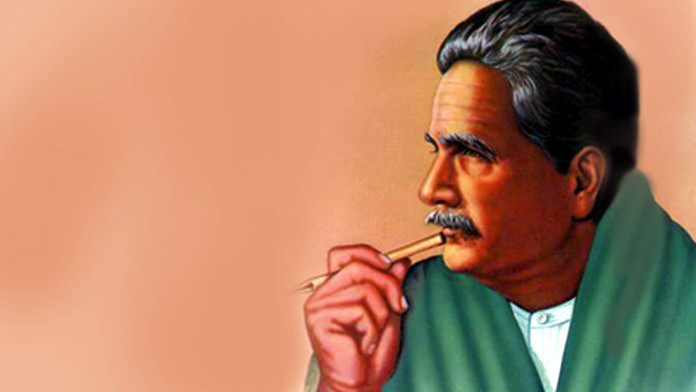

Two months ago, he handed me around a 300-page book, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam by Allama Muhammad Iqbal. No explanation. No nudge. Just slid it across the counter, looked at me, then at the book, and said, “This one will find you where you are.” Got the chills already and left for a qawwali section in the dargah for the first time ever.

A few days later, I began reading it at Delhi Airport, waiting for my flight to Kashmir. Aircraft taxied past like thoughts seeking clearance, each heading toward a different horizon, yet all lifted by the same unseen law. Iqbal’s first lecture unfolded two hours before my boarding. The book is not easy. It demands the kind of attention modern life no longer encourages. Iqbal dismantles ossified thinking, summons the courage for ijtihad, stitches together science and faith as though they had been cut from the same cloth all along. He writes as if belief and progress are not two runways but one.

By the time my boarding call came, I hadn’t finished. I was totally all in surely something in my coordinates had shifted. All I could recall was one line that my mentor, my friend, and my brother Tariq Banday used to quote from Iqbal:

“Sitaron se aage jahan aur bhi hain”, while I was walking towards my seat in the aisle.

Somewhere over the clouds, with the cabin lights pooling over the pages, the valley of Kashmir appeared below Harmukh, stern, and the arms of the Pir Panjal and a glint of Nun Kun, holding sunlight like a crown. It felt as if these mountains, eternal and wordless, were leaning in to listen to Iqbal with me. Page after page till the last line, I completed it in kind of one sitting.

I landed in Srinagar in late afternoon, and my friend Mudasir (Mudda) was waiting for me at the airport to take me back to where I belong Tangmarg, the place where I lived the majority of my childhood. The book came with me like a second pulse and a different me. The next day, I would walk past the trees near my home, and a sentence would rise not from memory, as if the trees had whispered it in my ears from the book, where Iqbal quotes Rumi:

“Divine Knowledge is lost in the knowledge of saints, and how is it possible for people to believe in such a thing.”

Tangmarg seemed complicit, whispering Iqbal’s ideas back to me, not in the language of print but in wind, water, and light.

Recently, I visited Delhi again, Nizamuddin again, JMC Emporium again, and Basit again. He was there, perched behind his fortress of leaning stacks. He didn’t ask. We didn’t talk. His smile said everything the kind of smile that says, “Told you.”

And somewhere I could still hear Iqbal again saying:

“Tu shaheen hai, parwaz hai kaam tera,

Tere samne aasman aur bhi hain.”