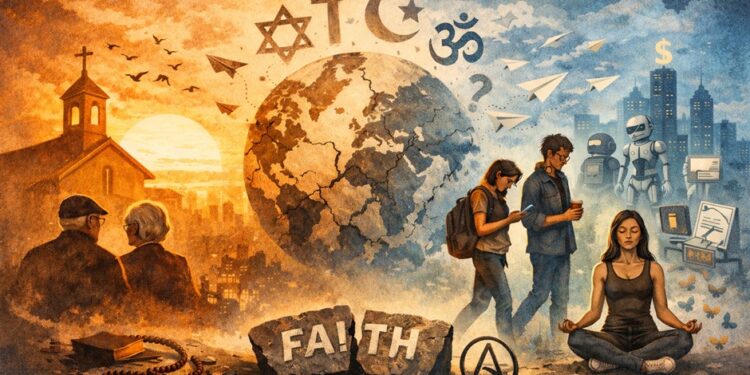

Across much of the world, religion is quietly losing its grip on younger generations. Compared to their parents and grandparents, today’s youth are far less likely to belong to an organised faith and far more likely to describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated, often called “nones”. This shift marks one of the most significant cultural changes of our time, reshaping how societies think about belief, identity, and meaning.

Large international surveys show that in dozens of countries, young adults are less religious than older generations. The decline is most visible in the United States and Europe, where religion has steadily moved from the centre of public life to its margins. Churches, once key social institutions, now attract fewer young people, while religious identity is increasingly seen as optional rather than essential.

Yet this trend is not universal. In parts of the Middle East and North Africa, religious practice among young people has remained strong and, in some cases, has even increased. These contrasts highlight an important truth: religion does not exist in isolation. It is shaped by history, politics, economic conditions, and social stability.

In recent decades, global conflicts and power struggles have deeply influenced how faith is perceived, particularly among the young. Prolonged wars, regional instability, and repeated interventions by global superpowers, often driven by energy control and strategic dominance, have entangled religion with politics and identity. In many regions, faith has been used to justify violence, assert power, or mobilise populations in proxy conflicts. For young people watching these events unfold through global media, religion can appear less like a source of peace and more like a tool of control. This perception has pushed many away from organised religion, while also contributing to radicalisation in conflict-affected societies.

In Western countries, the shift away from religion is especially pronounced. In the United States, roughly 30 to 40 per cent of Millennials and Generation Z say they have no religious affiliation. Similar patterns are visible across the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where being non-religious is increasingly common. However, this does not mean that most young people are atheists. The fastest-growing group is made up of those who simply do not identify with religious institutions.

Many young people now describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious”. They continue to search for meaning, ethics, and purpose, but prefer personal belief systems over formal doctrines, rituals, and hierarchies. Practices such as meditation, mindfulness, and individual reflection have replaced regular worship for many. Faith, where it exists, has become private rather than communal.

Upbringing plays a crucial role in this transformation. People who are not raised in a religious environment are unlikely to adopt faith later in life. As fewer parents pass on religious traditions, each generation becomes less connected to organised religion than the one before. At the same time, religious institutions have lost much of their social influence. Communities are weaker, lives are busier, and modern culture places greater emphasis on individual choice. Higher levels of education and rising incomes have also been linked to declining religious affiliation, particularly in Western societies.

Globally, the number of religiously unaffiliated people grew from about 1.6 billion in 2010 to nearly 1.9 billion in 2020, driven largely by changes in the West. Still, strict atheists remain a minority. In fact, atheists may form a smaller share of the world’s population in the coming decades, as religious communities, especially Muslim populations, tend to have higher birth rates. Demography, as much as belief, will shape the future of religion.

Some recent studies suggest that the decline in religious affiliation in the United States may be slowing. The youngest adults today report levels of religious engagement similar to those slightly older than them, hinting at a possible pause rather than a reversal of the trend.

As organised religion retreats from public life, it leaves behind a vacuum that is being filled unevenly by politics, technology, and growing anxiety about the future. Democracies already under strain are increasingly expected to provide not just governance, but meaning and moral direction. Climate change has introduced deep existential uncertainty, while the rapid rise of artificial intelligence has unsettled long-held ideas about work, purpose, and what it means to be human. In the absence of shared spiritual frameworks, many young people are left to navigate these challenges alone.

The decline of organised religion, then, is not merely a story about faith. It is a reflection of how modern societies are struggling to anchor hope, ethics, and belonging in an age of constant change.

The author is a painter, writer, and senior marketing professional with more than 25 years of experience working with leading semiconductor companies and can be reached at aijazqaisar@yahoo.com.