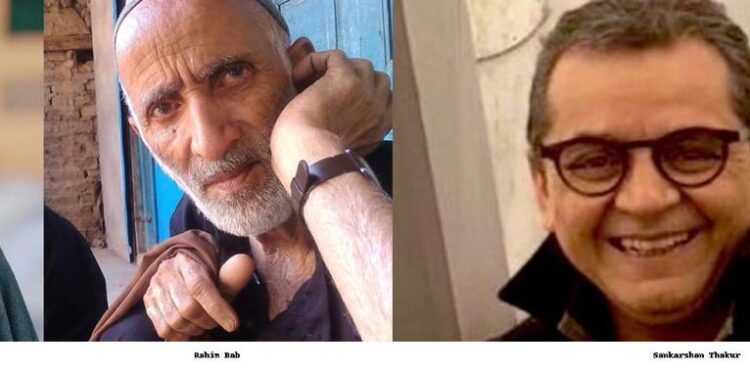

News and people who make it fascinate me since childhood. My courtship with the world of news is filled with both positive and negative experiences that I hold close to heart, as all of them helped shape me into the person I am today. These experiences include my grandfather introducing me to radio, Rahim Bab’s shop as a place to follow news, Gurjit Ma’am’s mentorship at All India Radio, Naeem Saheb’s hand-holding during my political stint with PDP, to Sankarshan Thakur’s Writings and this journey started quite early in my life.

I still remember sitting with my grandfather, listening to radio bulletins at various hours of the day. I was first introduced to Kashmiri Pandits as part of our society by my grandfather, as most Kashmiri news, aired from Delhi studios of All India Radio, was read by Pandit newscasters. He would often praise the way Kashmiri Pandits spoke and felt deeply sorry about their exodus from Kashmir.

My grandfather was a kind man. He had never seen the inside of a school; he wasn’t literate in the conventional sense, yet was wise enough to know the true value of education. Hence, he made sure I continued learning, no matter where the lessons came from. He nudged me to listen to the radio, but ensured that I stuck to news or educational programs.

However, he found cricket commentary intolerable. He was utterly aghast whenever he caught me listening to cricket over the radio, as he considered it a royal waste of time. He would exclaim, exasperated, “Zeenun kemen tam; toie chu rawrawan waqat.” (They’re the ones making the money, referring to the players, while you’re the one wasting your time.)

My grandfather died last year. He had a special fondness for traditional Kashmiri music, including the Chakri, along with the songs of the popular poet and Sufi saint Wahab Khar. An indelible memory I have is of my grandfather sitting in his favourite corner around midday with my grandmother, both completely absorbed by the music playing on the radio. Our closeness ensured that I ended up being part of those moments too, and it sparked my interest and curiosity for the “magic box”. Little did I know that one day I would get a chance to work for the radio station.

Cut to the 1990s. That era was overflowing with news in Kashmir, and the radio was our only reliable source of information. Occasionally, Urdu newspapers would arrive at our doorstep, and I loved flipping through them. My first brush with English newspapers came much later, and it was through an unlikely source: a neighbourhood shopkeeper we fondly called Rahim Bab. Rahim, who was very affectionate towards me, ran a small shop close to our home where I would sit for hours together, devouring old English newspapers he bought in bulk to wrap groceries for his customers. Wrapping groceries in newspapers was the commonplace sustainable practice in villages then, long before the onslaught of polythene packets ruined it for both us and the environment.

I hardly understood what I read, but the act of reading filled me with strange, inexplicable joy. A new world was opening before my eyes. Rahim Bab was gracious enough to let me flip through bundles of newspapers he brought from town. I was never scolded or asked why I loved reading; perhaps he assumed that I was simply curious. As I slowly waded through the stacks of papers one by one, I recall him sitting next to me, waving a ceremonial fly whisk to drive away flies, especially in summer.

Besides being a shopkeeper, Bab also worked as a chef on the side, cooking at small marriage parties and functions. Sometimes, he brought home a portion of cooked meat for me, and my tongue still salivates in remembrance of the taste. He was a reasonably skilled cook, one who happily took charge of the kitchen whenever there were functions at our home. Cooking was his passion.

Bab was fond of radio news too. All through the day, the radio in his shop continued blaring in the background, playing music or programs, while he tended with elan to the stream of friends who dropped by to chat, or the occasional customers. But the moment the news bulletin started, everything else stopped. Silence would ensue, and all listened intently. BBC, Voice of America, All India Radio, Radio Germany, Pakistan Radio – these were stations he tuned into most. Post the bulletin, he and his friends would turn the shop into a discussion floor, debating every issue with great interest.

One day, I overheard them talk about the possibility of a nuclear war between India and Pakistan and how such a war might affect the region. “But not our region”, they chimed in chorus, because our village, tucked away in the far-off corners of Tral in Pulwama, is surrounded by mountains dotted with natural caves. Rahim Bab told his friends that if ever, God forbid, such a war broke out, we could take shelter in one of those large caves deep in the forests. As a child, I was puzzled. Could I even walk that far? And what would happen to me if I couldn’t? Those thoughts lingered in my young mind.

I thought of Rahim Bab again during Operation Sindoor, when Pakistan’s defence minister announced a meeting of their National Command Authority (NCA), the body that decides on the use of nuclear weapons. Suddenly, the threat of war felt frighteningly real. Plus, I was in Srinagar, and the solace that came from hiding in that cave was out of the question. Now Rahim Bab is no longer with us. He passed away a few years before my grandfather. But his words and that memory remain etched in my heart. In hindsight, Rahim Bab’s shop wasn’t just a place to buy groceries; it was a hub of conversation that sparked curiosity, nurtured generosity, and opened a window to the world beyond my village.

The tradition that transcended his shop was my love for news and newspapers.

Whenever I got a chance to visit Shahar, as Srinagar city is fondly called across Kashmir, I would buy an English newspaper. For us, coming to Shahar was a luxury, not something everyone could afford. Most times, our visits were for medical reasons; travelling simply to unwind never occurred. Over the years, I tried to make sense of English news, thanks to my grandfather, who had introduced me to radio bulletins. Apart from Kashmiri news I listened to with him, I began tuning in to All India Radio’s midday English news, especially on holidays.

Slowly, changes emerged in my reading comprehension, and I began to understand what I read. With the help of a dictionary my father had bought me, I looked up new words and built my vocabulary, word by word. Later, when I moved to Srinagar for further studies, newspapers moved from being my main source of information to a way to ease stress. With the little pocket money I had, I bought national and local newspapers daily and read them cover to cover. It was a routine that lasted years. Looking back, I credit this habit of reading for helping me survive a difficult phase of depression – a sinking period which sometimes re-emerges as bouts of mental health struggles I face in the present. Since no support was forthcoming from anywhere else, I escaped my maladies through reading, and it helped me navigate one of the toughest times of my life.

In the period of 2006–07, I found myself in the newsroom of Radio Kashmir, thanks to my friend Shabir Mir, who was almost like an elder brother to me. Shabir, a fellow Trali who currently works with the J&K government, introduced me to Mrs. Gurjit Shahana Malik, an Indian Information Service (IIS) officer heading the Regional News Unit at Radio Kashmir, Srinagar. At the time, Shabir and I stayed together in Dalgate, and I suspect he knew of my passion for news.

Gurjit Ma’am, as I fondly called her, gave me an insignificant job but something I badly needed. It wasn’t much in terms of money, but it fetched me my first real earnings and helped me learn the value of being independent. She treated me like her own son – encouraging and pushing me forward. She often sent me out to cover press conferences and events. With no formal training in journalism, I initially found it overwhelming, but an inner resolve kept me going.

I recall covering press conferences of leaders like Omar Abdullah, Dr. Farooq Abdullah, Ghulam Nabi Azad, and Ghulam Mohammad Shah (G.M. Shah, popularly known as Gull Shah), among others. I also covered the Santosh Trophy football tournament held in Srinagar, all for Radio Kashmir news. Gurjit Ma’am mentored me through those early days, guiding me with patience and affection. She was a voracious reader and very interested in all I was reading. She’d ask me to share books with her, and I gladly did. Later, we sat for book discussions of our own. She passed away in 2017 at the age of 65.

When the internet became popular, affordable, and available at the tip of thumb, it opened vast resources for all those interested in reading, learning, or writing. I was no exception. I explored the internet, and later social media, for local, national, and international issues. It was a humongous shift that led to greater interest in the news.

For my mid-session internship, I joined one of Kashmir’s prominent newspapers, only to be shown the door by an editor who, for unfathomable reasons, simply didn’t want me around. I walked out that cold winter evening, head down, huddled in my long coat, feeling as if my entire world had collapsed, convinced of my inability to do meaningful work in life.

Without knowing what else to do, I ended up at the office of one of Kashmir’s prominent newspapers—The Kashmir Images. The paper is edited by the seasoned journalist Bashir Manzar, whose voice I first heard in Sheherbeen, the popular current affairs programme on Radio Kashmir, back in my village days. His nuanced, balanced, and realistic take on the issues of our place—delivered in chaste Urdu, still echoes in my mind.

I remember sending newsletters and small articles to Images while I was still in school, and Bashir Saheb would publish them. Yet, I had never met him in person until that day. Sitting in the editor’s chair, I told him how I had been thrown out of a newspaper with tears rolling down my face. I was in a panic, completely overwhelmed by deep anxiety. He consoled me, helped me regain composure, and made me feel that all was not lost.

Though I never worked directly with him at Images, his words of encouragement and quiet support helped me navigate the murkier waters of news and media. In many ways, Kashmir Images became my home, a place that would always publish my articles and opinion pieces whenever I sent them.

Bashir Saheb himself is a self-made journalist, hailing from a village in Tangmarg. Moderate, sane, and deeply intelligent, he continues to embody the kind of journalism our place desperately needs. He knows the struggles of newcomers and strugglers like me. Over the years, he has remained a go-to person whenever I needed clarity—whether about Kashmir or the wider South Asian region.

For my mid-session internship, I joined one of Kashmir’s prominent newspapers, only to be shown the door by an editor who, for unfathomable reasons, simply didn’t want me around. I walked out that cold winter evening, head down, huddled in my long coat, feeling as if my entire world had collapsed, convinced of my inability to do meaningful work in life.

Following that, I tried my hand with several news organisations, both local and national, but nothing stuck. A prominent national news agency, where I worked as a freelance journalist, refused to pay me a single rupee. At a local newspaper, I made endless calls, even on Eid, simply to collect my dues. When I was finally called to their office, on the pretext of payment, they tossed a few crumpled notes at me as if they were doing me a favour.

All these experiences left a bad taste. I stopped wooing mainstream journalism as a career, and I eventually re-routed towards a different path, still connected to news and newsmakers— politics and political communication.

Even though these career setbacks pushed me into depression, the world of news continued to enchant me. I decided to formally pursue a degree in journalism. So I landed in journalism school for my master’s. I did reasonably well academically, and going to university infused me with the confidence, opening doors to new opportunities and ways of learning.

While pursuing my degree, I joined a few news organisations as an intern, alongside my stint at Radio Kashmir. Life was chaotic but fulfilling, as I was finally chasing my passion. Somewhere on the way, I joined the media department of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), which served as the main opposition party in J&K. Here, I worked closely with Naeem Akhtar, the party’s chief spokesperson and one of its foremost thinking heads. He had taken on the role of my supervisor with a promise to facilitate my growth. I learnt a great deal from him.

To meet his and the party’s expectations, I worked long hours mindlessly, burning the candle at both ends, skipping meals at times and ended up completely drained. The party was a pioneer in professionalising communication strategy, and I take immense pride in being part of the process that created the foundational structures for it. I even joined the government for a bit before eventually stepping away from politics. Looking back, that phase was both a period of learning and one that shaped me into who I am today: calm, confident, motivated, and capable of taking on challenges without waiting for support.

Naeem Saheb was a hard taskmaster. He was affectionate, lovable, and friendly, but equally tough to work with. Having served the government for decades, he carried invaluable experience and discipline, leaving little room for nonsense. I worked with him on two major elections, one parliamentary, the other assembly – one that eventually brought PDP back to power in 2015. That period emerged as a game-changer for me. I sharpened my skills in political PR writing and absorbed valuable political lessons along the way. I learned that in politics, words can win battles but only if they are honest and disciplined.

My grandfather, Rahim Bab, and Naeem Saheb are some pole stars who shaped my sense of news and helped me discover my passion. I haven’t paused to check how many milestones I have covered, but what gives me peace is knowing that I discovered my true calling in this journey.

Many people have not only shaped my writing skills but also given me invaluable insights into how one should approach life and contribute ideas that make politics and society better. They helped me realise that real politics is not about reacting emotionally, but about finding thoughtful approaches that address issues, set directions, and create a roadmap for a civilised society to function, prosper, and find happiness.

Among these influences, two mentors stand out: Rauf Rasool, a senior journalist, and Parvez Majid Lone, a journalist-turned-academic. Both are seasoned professionals with nearly two decades of experience in journalism, teaching, and writing. Learning from them has been one of the greatest privileges of my journey.

One of my biggest challenges and one I continue to work on has been communication in English. Public speaking once felt impossible, and even my everyday conversations lacked confidence. This struggle stemmed largely from the kind of schooling and environment I grew up in, where such skills were neither taught nor encouraged. Like many others from government-run schools, I faced this barrier head-on.

Over time, I improved, thanks in large part to Gurmeet Kaur, a seasoned academic and English language trainer. I met her while preparing for my twelfth-standard board exams, and she became a pivotal figure in my growth. With patience and without judgment, she pushed me to confront the gaps in my communication and gave me the confidence to express myself. For that, I remain deeply grateful.

This article would be incomplete without mentioning one more person who has influenced me deeply, even though I never met him. I only came to know him and learnt from him through his words. Writings of Sankarshan Thakur, the editor of The Telegraph, who passed away a few days ago, on Kashmir and beyond Kashmir were my lessons. Fearless, compassionate, and profoundly humane, he weaved magic with words. A master of his craft, his prose carried the rhythm of poetry and his storytelling was infused with honesty and grace.

His passing leaves a void, not only in journalism but also in the larger conversation about Indian politics. Through his repeated journeys across Jammu and Kashmir, he listened without judgment and gave space to people’s truths. What he leaves behind is an archive of rare depth, an invaluable resource for anyone trying to understand this land in all its complexity. For Kashmiris, whom he cared for, loved, and respected, his writing reflected the bond in each word.

With Sankarshan’s passing, Kashmir loses yet another amplified voice. It is hard to imagine anyone from mainland India who could match his class, his words, and his honesty in telling our story. In the times we live in, it feels unlikely that there will ever be a replacement. We are in for a long haul, and that worries us even more.

Through Sankarshan Thakur’s words, I learned to see Kashmir and the rest of India with compassion. Similar to Eklavya, who learnt indirectly from Dronacharya, Sankarshan Thakur was my revered teacher from afar. But unlike Dronacharya, he was oblivious to my existence. And he didn’t ask me to cut my thumb as his Guru Dakshina offering.

The writer is a public relations professional, the recipient of the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP).

Courtesy www.jkpi.org