The Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) is one of Asia’s largest contemporary art events, and its sixth edition takes place from 12 December 2025. Held biennially in Fort Kochi, Kerala, the Biennale has established itself as a significant platform for global and regional artistic exchange.

One of the key components of the Biennale is the Students’ Biennale (SB), a major parallel educational initiative of KMB. The Students’ Biennale showcases the work of emerging art students from across India and runs concurrently with the main exhibition. For the sixth edition, scheduled from December 2025 to March 2026, the Students’ Biennale will be presented across multiple venues, offering young artists an important opportunity to exhibit their work and gain visibility within a large-scale contemporary art festival.

To facilitate outreach and participation from diverse regions of the country, this year the Students’ Biennale was divided into seven zones. Each zone was supported by an independent curatorial team responsible for developing projects and presenting them at the Kochi Students’ Biennale.

Khursheed Ahmad and Salman Bashir Baba were nominated as curators for the Western Himalaya Zone. The two artists from Kashmir have brought together students from across the region, creating a platform for emerging voices from the Western Himalayas to participate in the Students’ Biennale 2025-26.

Students applied through an open call announced by the Biennale Foundation on its official online platforms. Art students from across India were eligible to apply to this open call. From the Western Himalaya zone, twenty applications were shortlisted and forwarded to the curatorial team for review. The curators evaluated the submissions and conducted online interviews and meetings with all shortlisted applicants.

A three-month period was allocated to the curators to conduct field visits within their respective zones. During this phase, the curatorial team undertook research visits to various art colleges across the region. In addition to institutional outreach, personal networks were also utilized to connect with students. In regions such as Himachal Pradesh and Jammu, the curators contacted faculty members at art colleges, who then connected them with students; however, in some cases, student responses were delayed or did not materialize.

In Ladakh, several key cultural and educational organizations played an important role in facilitating connections between the curators and local art students. These included the Ladakh Art and Media Collective, Achi India, and the Central Institute of Buddhist Studies (CIBS).

Following this multi-stage selection process, ten projects from four states were finalized for the Students’ Biennale. These included three projects from Kashmir—comprising one group project and two individual projects. In Kashmir, a six-day workshop was conducted, and the outcomes of this workshop form part of the exhibition at Kochi. From Ladakh, three projects were selected, including one group project. Himachal Pradesh contributed two group projects, while one project was finalized from Uttarakhand.

After finalizing the projects, the curatorial team visited the exhibition sites in Kochi. The Students’ Biennale operates through dedicated exhibition spaces exclusively allocated for student projects. Following site visits, the curators jointly engaged in the curation process, meeting to plan and finalize the spatial allocation for each project.

VKL Warehouse, BMS Warehouse, and Arthshila Kochi, Mattancherry, served as the exhibition venues where works from all zones across India were displayed. Projects from the Western Himalaya Zone were presented across these three venues.

The Students’ Biennale positions student projects alongside the main Biennale exhibitions, placing emerging practitioners within the broader framework of a major contemporary art event.

The Western Himalaya Zone curatorial project was titled “for now”, the concept states that “the project foregrounds an atlas of emotions from the Western Himalayan region—Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Ladakh, and Jammu & Kashmir—bringing together narratives that reflect on what it means to live, see, feel, and create within these spatial folds. Shaped by layered memories, fragile ecosystems, and the precarious horizons of mountain landscapes, the project gathers stories rooted in lived experience. Through subtle intimacies of everyday life, the works traverse shifting axes of social, political, and ecological existence, offering viewers textured encounters with place.

The Western Himalaya Zone curatorial project was titled “for now”, the concept states that “the project foregrounds an atlas of emotions from the Western Himalayan region—Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Ladakh, and Jammu & Kashmir—bringing together narratives that reflect on what it means to live, see, feel, and create within these spatial folds. Shaped by layered memories, fragile ecosystems, and the precarious horizons of mountain landscapes, the project gathers stories rooted in lived experience. Through subtle intimacies of everyday life, the works traverse shifting axes of social, political, and ecological existence, offering viewers textured encounters with place.

Moving at an experiential pace, the participating students reflect on lived realities, everyday rituals, and embodied practices, documenting space as speculation, perception, and interpretation. for now, holds a quiet insistence on the provisional, the partial, and the present. It gestures toward temporality that resists closure—an ongoingness attentive to the weight of the passing instant. Rather than fixing meanings or asserting certainties, the project remains with what is fleeting, with what can still be felt. It invites viewers to recognize the present as fragile, acknowledging that presence itself is subject to shift and transformation.

Across the works, drawings tracing women’s experiences—from the Bombay local trains to the riverbanks of Roorkee—raise questions of femininity, mobility, and labor. A performance embodies “the eye,” reversing the ethnographic gaze and challenging conventional positions of observation and inquiry. A chair constructed from residual planks, placed before a suspended windowpane salvaged from a demolished house, becomes a charged site of translation and tension. Elsewhere, the figure of the fish emerges as both myth and metaphor. Indigo sculptures, Thangka paintings, and assemblages of papier-mâché horns suspended above amorphous clay forms trace connections between shifting temporalities, changing ecologies, and layered historical narratives. Each work reveals how conflict within these terrains folds into the quotidian, foregrounding urgent concerns of ecology, displacement, and visibility. Collectively, the artists articulate ways of knowing that are locally grounded—rooted in lived realities rather than imagined from a distance.”

Participation in the Students’ Biennale plays a significant role in the artistic and professional development of students. The platform provides them with the opportunity to visit the Biennale, engage with peers and artists from different regions of India, and build networks across diverse artistic communities. It also becomes an integral component of their art education, enabling them to encounter a wide range of artworks and practices, interact with varied audiences, and articulate their own artistic positions.

Reflecting on the curatorial approach, Khursheed Ahmad and Salman Bashir Baba stated:

“We come from marginal peripheries where mainstream art has limited reach, despite the presence of diverse art communities across the region. This marginality significantly affects art education, and students often lack exposure to major contemporary art events. One of the key challenges for us was to bring forward projects that could meaningfully resonate with the larger framework of the Students’ Biennale. What is often missing is exposure, and the Students’ Biennale provides a vital platform—bringing students together on a national and international stage through the collective efforts of curators, participants, and the Biennale Foundation.”

The curators observed that the site plays a crucial role in shaping the meaning of the works, particularly when they are exhibited in different spaces with distinct contexts that influence their interpretation and understanding. The projects were appreciated for both their curatorial rigor and their regional significance.

The curators observed that the site plays a crucial role in shaping the meaning of the works, particularly when they are exhibited in different spaces with distinct contexts that influence their interpretation and understanding. The projects were appreciated for both their curatorial rigor and their regional significance.

These two artists from Kashmir, as curators, became an integral part of the Student Biennale’s curatorial process. Their involvement marks a significant beginning—one that is likely to inform and inspire future projects. The experiences gained through this process will be carried forward and shared with other students and artists within their communities.

Reflecting on the selection process and their overall experience of curating the Western Himalaya Zone, the curators articulated their approach as follows. They emphasized that projects were selected based on key criteria, including technical skill, conceptual clarity, depth of research, and evidence of artistic growth and learning among the students.

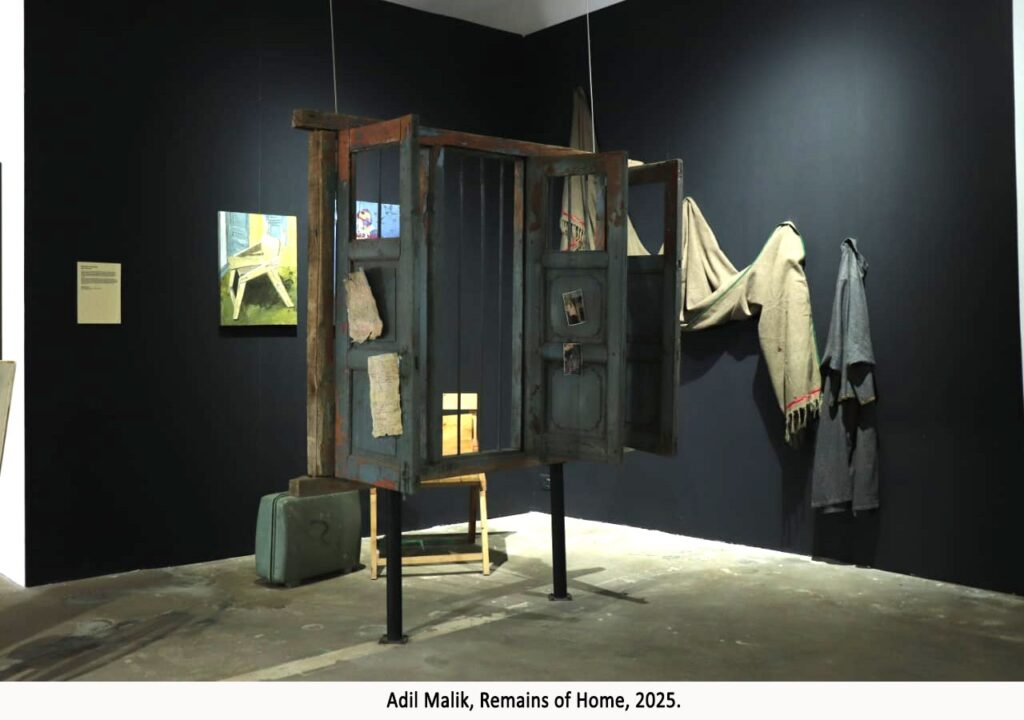

One such project from Kashmir, titled Remains of Home, examines the site of the artist’s former home, which was demolished due to road-widening initiatives. The work explores how memory persists when physical structures disappear, and how these memories permeate one’s sense of self. The artist unfolds multiple layers of “home” through a series of gestures: a self-portrait, a chair constructed from wooden planks salvaged from the demolished house, and visual references to childhood memories such as toys, photographs, and land ownership documents. An actual window from the house was also installed at the exhibition venue. Together, these elements form a visual essay that reflects on loss, memory, and belonging, revealing how the artist conceptualizes and reconstructs the idea of home.

The curators further reflected on the challenges of working within the Himalayan region, particularly in contexts such as Kashmir, where issues of mobility, accessibility, and infrastructural disconnection remain persistent. Despite these constraints, sustained engagement with the region and reliance on personal networks facilitated meaningful connections. Traveling across the Western Himalayan belt—from Kashmir to Leh, and from Uttarakhand to Shimla—never felt unfamiliar. Instead, these journeys evoked a shared sense of home, charged with emotion and unfolding through common narratives encountered across locations.

This sense of continuity was evident not only in the artworks but also in the curatorial process itself. The Himalayas emerged as a living body—its inhabitants forming the circulating blood that connects each organ—binding diverse geographies through shared histories, affect, and lived experience.