Insha Manzoor, an artist from Kashmir, is presenting her work in the ongoing exhibition Ski(e)n: Remembering through Performance and Thread at Dhoomimal Gallery, Connaught Circle, New Delhi. The exhibition showcases two artists—Abhina Vemuru Kasa and Insha Manzoor—both alumni of the Royal College of Art.

Abhina Vemuru Kasa’s practice interrogates femininity, memory, ritual, and the body through powerful visual and performative languages. The exhibition is curated by Jyoti A. Kathpalia, Associate Professor, art critic, and curator.

Insha Manzoor is a multidisciplinary artist, working with installation, video, painting, etc. Her recent exhibition in Dhoomimal Gallery shows her diverse approach towards art making; her painting and installation are two different approaches, but consist of a deep meaning of place, self, belonging, and space. Through which artist presents her personal reflection as a being, grown with many constituents of cultural objects of identity.

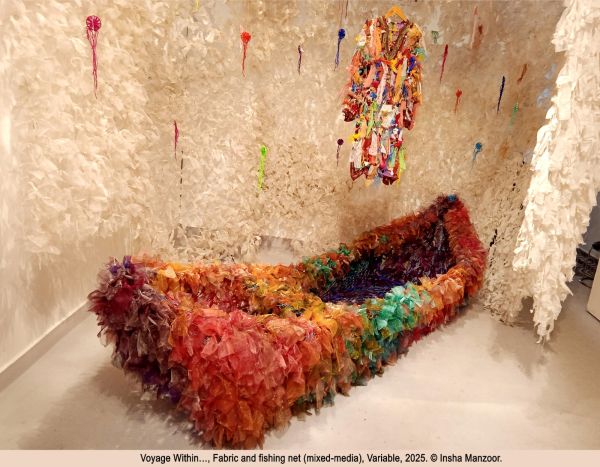

The installation showcases the knotting of different pieces of colored ribbon, which seems physical and merges the colors when seen from a distance. Extremely shows the intense colors, and many subjects that the artist presents, from the wearing cloth phiran to her self-portrait. The paintings show a different approach with freely using the brush and a thick amount of colors, representing symbolically, many appellations like home and pambch.

Rooted deeply in the lived experiences of growing up in Kashmir, the artist’s work reflects a sustained engagement with memory, loss, and cultural inheritance. Witnessing the gradual marginalization of traditional crafts such as namda, the artist views art as a vessel for preservation and resistance—holding collective histories, rituals, and narratives that risk disappearance. Kashmiri crafts recur within the practice not as nostalgic references, but as dynamic cultural forms capable of articulating resilience, interconnectedness, and identity.

Symbols and icons drawn from Kashmiri culture function as layered carriers of memory and political meaning. Through repetition, material exploration, and recontextualization, these elements are transformed into reflective spaces that speak to shared humanity amid conflict. The artist’s textile installations, textile-based works, and paintings emerge from a shared conceptual ground: textiles embody intimacy, labor, and remembrance, while painting offers a quieter, introspective register. Together, these mediums form a continuous dialogue.

As Jyoti A. Kathpalia notes, “Insha Manzoor’s art unravels and reknits the skeins of her lived milieu through nostalgia and memory, offering a glimpse of a more humane world. At its core, her practice is a search for home—understood not merely as a physical space, but as a site of security, comfort, and belonging. Through her works, Insha seeks to recreate this feeling by employing motifs, symbols, cultural signifiers, and icons that gesture toward a lost or fragmented home.

As Jyoti A. Kathpalia notes, “Insha Manzoor’s art unravels and reknits the skeins of her lived milieu through nostalgia and memory, offering a glimpse of a more humane world. At its core, her practice is a search for home—understood not merely as a physical space, but as a site of security, comfort, and belonging. Through her works, Insha seeks to recreate this feeling by employing motifs, symbols, cultural signifiers, and icons that gesture toward a lost or fragmented home.

In this exhibition, she returns to community, craft, and labour—namda, knots, pheran, boats—to reconstruct the self through the textures of memory, place, and regional rootedness. Her work articulates a strong sense of self that connects past, present, and future. In doing so, the exhibition becomes an invitation for viewers to weave their own narratives, reflect on the layered nature of existence—personal yet collective—and begin again, from the bare skin.”

During our conversation, we engaged in a thoughtful exchange of questions with the artist.

Can you describe your experience of participating in this exhibition? How did it come about, and how did the curator first contact you? Are there any particularly memorable moments you would like to share?

My participation in this exhibition came about through a collaborative initiative with my batchmate from the Royal College of Art. We had planned a duo show and were jointly developing the proposal. She was already in touch with a curator due to her previous participation in a group exhibition at the India Habitat Centre. Through this connection, we both submitted our proposal to her for an art consult, and the show was initially approved.

Unfortunately, around that time, Sidharth Tagore passed away, and the exhibition was cancelled. However, our curator, Jyoti Kathpalia, later approached Dhoomimal Art Gallery with the same proposal. The gallery responded positively, and that is how this exhibition eventually materialized.

The experience has been deeply encouraging. Connecting with a gallery of such long-standing reputation has been both affirming and motivating. It has been a meaningful moment in my artistic journey, and I hope this association will open new directions and opportunities for my practice in the future.

You have mentioned that certain Kashmiri crafts, such as namda, are losing their traditional charm. How does your art practice revisit, reinterpret, or critically engage with the traditional arts of Kashmir?

Growing up in Kashmir, I witnessed profound changes in the place I call home—changes where the narratives of my community, our shared heritage, and traditional art forms were gradually pushed to the margins. This awareness shaped my understanding of loss, not only of physical spaces but also of collective memory, craftsmanship, and ways of storytelling that had once been integral to everyday life.

Through my art practice, I consciously revisit and reinterpret these traditional forms as a way of preservation and resistance. I realized that art could become a vessel to hold what might otherwise disappear—collective histories, legacies, and the quiet labor embedded in craft practices. Like many artists, my practice has evolved in phases, and over time, I have developed a body of work in which Kashmiri craft recurs because I believe traditional crafts have the power to transform material into profound cultural statements and convey themes of resilience and interconnectedness. My works merge rituals, storytelling, dying craftsmanship, and history to provoke questions, spark dialogue, and create spaces of reflection around identity, resilience, and remembrance.

Your use of symbols and icons drawn from Kashmiri culture reflects a strong relationship with place. How do your lived experiences shape your artistic process, and how have your years of art education influenced your current practice?

My bond with Kashmir is deeply personal—I belong to it, and it has shaped the way I think and create. I spent my childhood in the natural mystic background, embracing the snow-white lambs, playing with pebbles on the river-sides, which gave birth to the art of questioning about the existence of self and its purpose while searching for love for one’s own self and for a way of life without conflicts. Growing up in Kashmir also meant growing up surrounded by art, culture, history, and poetry, which naturally inform the symbols and icons in my work.

Alongside these lived experiences, my years of art education have played a crucial role in shaping my practice. Over time, I encountered some incredible mentors who shaped my artistic practice, such as Shyam Lal from Kashmir, Harsh Vardhan from Jammu, Sanchayan Ghosh from Santiniketan, and John Strutton from the Royal College of Art, London, and many more. They all contributed to my journey in distinct ways. They helped me question, unlearn, and reframe my understanding of material, form, and concept.

Together, my lived experiences and formal training have allowed my practice to evolve into one that is both intuitive and critically grounded—where memory, place, and personal history intersect with contemporary artistic inquiry.

How do you interpret the symbols and icons that have reshaped the social and political realities of Kashmir since the onset of conflict?

I see these symbols and icons as layered carriers of memory, meanings, and resistance. In my practice, I approach these symbols as lived and emotional realities. I reinterpret them through material and repetition to reflect the social fabric and personal psyche. By doing so, I aim to open spaces for reflection—where these icons can be seen as reminders of collective memory, resilience, shared humanity, and the quiet persistence of life amid uncertainty.

Can you explain the relationship between your textile installations, textile-based works, and your paintings? How do these different mediums inform and influence one another?

My textile installations, textile-based works, and paintings are deeply interconnected and evolve from the same conceptual ground. Textiles are integral to my thinking because they carry memory, labor, and intimacy—qualities rooted in domestic spaces, ways of remembrance, and lived experience. In turn, painting allows me to distil these ideas into a more meditative, introspective language.

Together, these mediums constantly inform one another: installations create immersive, bodily experiences; textile works hold narrative and memory; and paintings offer a quieter, reflective space. Rather than functioning separately, they form a continuous dialogue—each medium expanding the emotional and conceptual possibilities of the others.

What projects are you currently working on, and where are you based at present? How do you assess the current development of contemporary art practices in Kashmir?

At present, I am working on several projects that are in different stages of development, including large-scale installations intended for presentation on international platforms. These works continue my exploration of material, scale, and immersive experience.

I am currently setting up my studio in Mattan, Anantnag, Kashmir, which allows me to work closely with my subjects and engage more deeply with materials connected to questions of identity. I value movement in my process—I like to explore, travel, and learn, and then return to my own space to reflect and develop the work.

In terms of contemporary art practices in Kashmir, I feel the ecosystem is still evolving. While there is creative potential, there is a need to critically examine our premises—such as access to platforms, discourse, and sustained institutional support—to enable a more robust and nuanced development of contemporary art in the region.

Traditional arts have increasingly been affected by innovation and technology. Your use of cultural objects often suggests these transformations, and at times you appear to deconstruct their established meanings—for example, through the use of the phiran. How do you reflect on this approach in your practice?

In my practice, I see innovation and technology not as forces that simply replace tradition, but as realities that reshape how cultural objects are understood and lived with today. Traditional forms like the phiran carry deep emotional, social, and historical meanings. By deconstructing or recontextualizing such objects, I am not attempting to strip them of their essence. Instead, I aim to reveal the layers they have accumulated over time. When the phiran appears in my work, it moves beyond its functional identity to become a metaphor. This process allows me to question what is preserved, what is transformed, and what is lost when tradition encounters innovation.

Through this approach, I try to create a dialogue between past and present, craft and concept, intimacy and disruption. The work invites viewers to reconsider familiar cultural symbols not as fixed or nostalgic forms, but as living entities that continue to evolve, reflect, and respond to contemporary realities.