Art history is often divided into neat periods for convenience, yet the reality is far more fluid. Few distinctions cause as much confusion as the one between Modern Art and Contemporary Art. Both appear experimental and revolutionary, but their intentions, intellectual foundations, and historical contexts differ profoundly. The line separating the two is thin, yet it reshapes the very purpose of art.

Before Modern Art emerged in the late nineteenth century, the art world was dominated by what is known as Traditional or Academic Art—an era stretching from Classical Antiquity through the Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Academic Realism. Art was governed by strict rules of proportion, perspective, anatomy, and idealized beauty. Artists served religion, royalty, and the aristocracy, and their mastery was measured by their ability to imitate visible reality. Painting was expected to function as a “window to the world,” and institutions such as royal academies dictated which subjects were worthy of representation.

The invention of photography, the upheaval of industrialization, and the spread of scientific rationalism disrupted these centuries-old assumptions. If a camera could perfectly capture reality, why should art remain bound to imitation? This tension bred the beginnings of Modern Art—not as a gentle evolution from tradition but as a radical rupture.

The distinction between pre-Modern and Modern Art is greatly visible but, to separate Modern from Contemporary Art is a bit complicated but in some aspects the difference is huge. We can say that the most basic distinction between Modern and Contemporary Art is chronological. Modern Art generally spans from the 1860s to around the 1970s, while Contemporary Art begins in the 1970s and continues to the present. Modern Art arose in response to the rapidly changing conditions of industrial life: urban growth, colonial encounters, new technologies, and shifting philosophies. Artists no longer wanted to simply mirror the world; they sought to express how it felt. Contemporary Art, by contrast, developed in a world shaped by globalization, digital technology, mass media, identity politics, ecological crisis, and increasingly, artificial intelligence. The transition between the two is not marked by a specific year or movement—artists working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including Minimalists, Conceptual artists, and performers, sit precisely on this boundary, where Modern sensibilities dissolve into Contemporary practice.

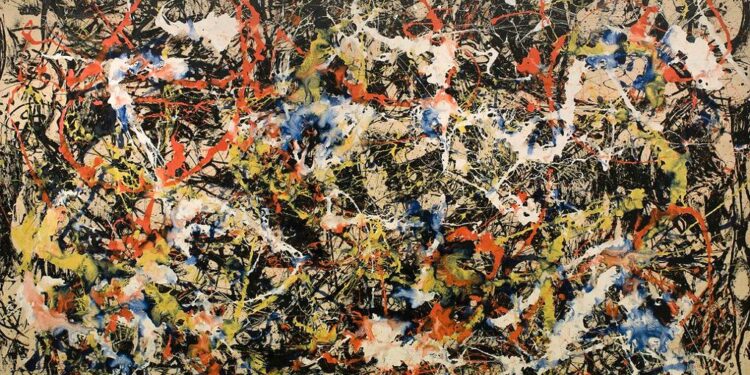

Philosophically, Modern Art was animated by a belief in universal truths. Artists searched for pure languages of color, form, and structure—whether through Cubism’s fractured vision, Abstract Expressionism’s emotional universality, or Suprematism’s quest for absolute geometric clarity. The modern world energized a faith in progress, originality, and the heroic individual artist.

Contemporary Art rejects the idea of a single universal truth. It embraces multiple identities, marginalized voices, cultural hybridity, and contradictory histories. Instead of seeking a singular meaning, it questions who constructs meaning in the first place. This shift—from certainty to complexity—forms one of the most defining differences between the two.

Modern artists often responded to society indirectly, using symbolism, distortion, or formal experimentation even when dealing with themes such as war or alienation. Picasso’s Guernica, for instance, is deeply political yet rooted in Modernist aesthetic exploration. Kandinsky’s abstractions were spiritual in intention rather than socially interventionist. Contemporary artists tend to engage society directly, addressing issues such as gender, caste, race, migration, digital surveillance, consumerism, or climate change. Art becomes an active participant in public discourse rather than a detached reflection. The gallery becomes a space of debate, resistance, and collective questioning—a shift from aesthetic autonomy to ethical engagement.

The materials and mediums used also illustrate this change. Modern artists pushed the limits of painting and sculpture but largely stayed within the realm of traditional art objects—oil on canvas, bronze, wood, or printmaking. Their innovations were primarily stylistic. Contemporary artists, however, treat anything as a possible medium: video, sound, digital projections, performance, found objects, waste materials, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, NFTs, or social media interactions. Sometimes the artwork becomes process rather than product—an experience, a conversation, or a temporary intervention rather than a collectible object. This move from object-based art to concept- and experience-based practice marks one of the clearest technical divergences.

The identity of the artist has transformed as well. In the Modern era, the artist was conceived as a solitary genius, a visionary rebel challenging tradition—figures such as Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, and Pollock embody this mythology. Contemporary artists often function as researchers, collaborators, social facilitators, or political commentators. Many projects involve scientists, activists, programmers, or entire communities. Personal authorship blurs; the artist becomes embedded within society rather than standing apart from it.

Likewise, the relationship with the viewer has shifted. Modern Art invites contemplation: the viewer looks, interprets, and emotionally responds. Contemporary Art frequently requires participation: walking through immersive environments, triggering sensors, interacting with performers or digital interfaces, or contributing personal data and stories. The viewer becomes a co-creator of meaning.

Institutionally, Modern Art rose alongside the establishment of museums, national galleries of modern art, avant-garde salons, manifestos, and a new class of critics. These shaped the intellectual foundations of modernity. Contemporary Art exists within a globalized, commercialized ecosystem—mega-galleries, biennales, international art fairs, private museums, corporate patrons, and online platforms—allowing art to move across borders, cultures, and markets with unprecedented speed.

The boundary between Modern and Contemporary Art is best understood as a transitional zone inhabited by movements such as Minimalism, Conceptual Art, Land Art, and early Performance Art. These practices shifted the focus from form to concept, from object to idea, from timeless aesthetics to time-bound realities. Modern Art asked, “How can art be new?” Contemporary Art asks, “Why must art exist at all and whom does it serve?”

In India, this line is especially fluid. Modern masters like M. F. Husain, S. H. Raza, Tyeb Mehta, F. N. Souza, and Ram Kumar shaped the evolution of Indian art, and their influence remains deeply embedded in contemporary practices. Today’s Indian artists grapple with postcolonial memory, urbanization, caste and gender politics, globalization, technology, and ecological anxiety—often blending Modernist formal concerns with Contemporary social engagement.

Ultimately, the difference between Modern and Contemporary Art is not merely a matter of dates. It is a shift in philosophy, society, materials, and purpose. Modern Art represents a great break from tradition, an attempt to redefine how we see. Contemporary Art represents a deeper questioning of reality itself within a complex, globalized world. While Contemporary Art emerges from Modern Art’s innovations, it carries the conversation forward—from form to meaning, from seeing to participating, from aesthetics to responsibility. The line separating them is thin, but it marks a profound transformation in what art is and what it strives to do.