Srinagar: The Guryul Ravine in Kashmir—home to one of the world’s most complete fossil records of the Permian–Triassic mass extinction—has been declared a national geo-heritage site by the Geological Survey of India (GSI), recognising its global scientific value and extraordinary preservation of 252-million-year-old geological history.

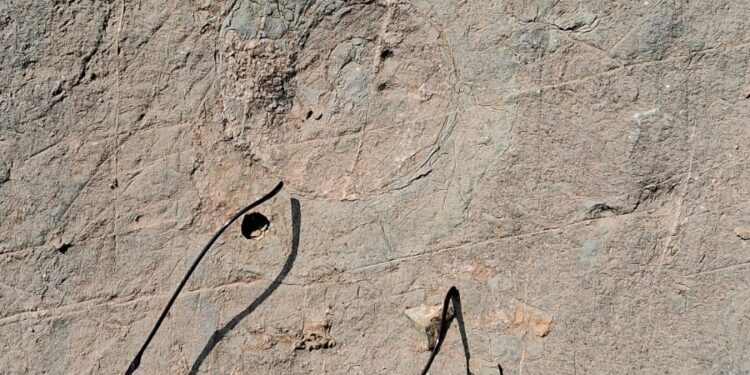

The fossil-bearing section at Guryul Ravine records the “Great Dying”, the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history, when nearly all life forms vanished. Located at Vihi in Khanmoh on Srinagar’s outskirts, the site also preserves traces of what scientists believe could be the world’s earliest documented tsunami within its one-metre-thick boundary section.

What makes Guryul Ravine exceptional, experts said, is its 3-metre-thick boundary section, far larger than the globally known Meishan section in China, which measures just 27 cm. This extensive thickness provides a clearer, uninterrupted geological timeline of the extinction and recovery phases.

Speaking to the news agency KNO, Mohsin Noor, Senior Geologist and Nodal Officer for Guryul Ravine, said the section remains unparalleled in the region and holds critical clues about ancient climate, biodiversity collapse, and geological transitions.

“Guryul Ravine marks the exact Permian–Triassic boundary and contains one of the world’s most detailed records of the ‘Great Dying.’ Its 3-metre composite boundary makes it scientifically more significant than the 27-cm Meishan section in China,” he said. “The layers here also preserve the earliest known tsunami deposits, making this site globally unique.”

Noor said Kashmir hosts exceptional geological diversity spanning vast time periods. “The Guryul Ravine at Khanmoh is among the Valley’s most significant geological sites, spread over 9.8 lakh square metres with a face length of over 1.4 kilometres in the Zabarwan foothills,” he said.

The geologist said the site’s “fascinating fossils” have attracted global scientific attention and strengthened its potential as a major geo-tourism destination.

Rare invertebrate fossils collected from the Ravine are preserved at the SPS Museum in Srinagar, and also at the Geoscience Museum, Department of Geology & Mining, J&K, located in Budgam. Noor was also an active member in the establishment of the Geoscience Museum.

The Permian rocks of the Kashmir Himalayas exhibit striking lithological variation—from fluvio-glacial and volcanic deposits to continental and marine formations—making them crucial for scientific research. The Ravine preserves an uninterrupted sequence across the Permian–Triassic boundary, including mixed fossil assemblages marking key climatic and biological shifts.

“This fossiliferous zone is among the world’s best-known Permian–Triassic type sections, home to an illustrious faunal assemblage of marine and terrestrial fossils that offer a biological window into the mass extinction event,” the Nodal Officer said.

While similar boundary sections exist in Iran and China, Noor said they lie in remote terrains. “Guryul Ravine is easily accessible, and its proximity to markets gives it unique global significance.”

The site’s rock formations show a transition from arenaceous to argillaceous and carbonate sequences. The earliest Triassic layers begin with the ammonoid Otoceras woodwardi, a key marker fossil.

Noor recalled that during an international geological conference in Jammu in 2007, experts raised concerns over quarrying at the site. This prompted the Department of Geology and Mining to stop quarrying, restrict access, and fence the area to protect the fossil zone.

The Guryul Ravine fossil park is currently maintained by the Department of Geology and Mining through the District Mineral Foundation Trust (DMFT), Srinagar.

“The Guryul Ravine is nature’s library—holding secrets of historical geology and ancient climate change,” the geologist said, adding that the site is open to tourists, students, and researchers from across the world.